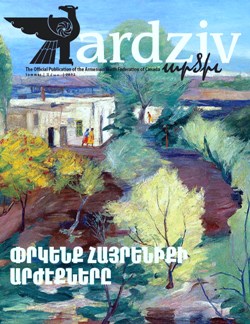

The Shuga Unplugged: Farmer’s Markets in Armenia

By: Lena Tachdjian | Posted on: 14.10.2014Warning: Undefined array key "ssba_bar_buttons" in /home/u108981792/domains/ardziv.org/public_html/wp-content/plugins/simple-share-buttons-adder/php/class-buttons.php on line 602

Warning: Undefined array key "ssba_bar_buttons" in /home/u108981792/domains/ardziv.org/public_html/wp-content/plugins/simple-share-buttons-adder/php/class-buttons.php on line 602

Warning: Undefined array key "ssba_bar_buttons" in /home/u108981792/domains/ardziv.org/public_html/wp-content/plugins/simple-share-buttons-adder/php/class-buttons.php on line 602

Warning: Undefined array key "ssba_bar_buttons" in /home/u108981792/domains/ardziv.org/public_html/wp-content/plugins/simple-share-buttons-adder/php/class-buttons.php on line 602

When I went to my first farmer’s market in Canada, I did not know what to expect. What I found was a clean and organized system, with labeled produce from every farmer laid out on a table with clear prices. It was a great way to meet people actually growing food, to see what was in season and, of course, to learn about fruits and vegetables I had never seen or eaten before, usually at much better prices.

When I try to describe an Armenian farmer’s market, or shuga, I find that I contradict myself constantly. After a long day of meeting farmers at the shuga to pick up produce for Go Green Armenia, I am sometimes bitter at how disorganized and chaotic they are. People keep their produce on the floor, yell out what they have in the smoke filled-air, and literally push you out of their way as they rush off to different booths. There is also everyone’s greatest fear: the men steering the massive carts to move around heavy produce who have a “If you don’t see us coming behind you and move, we will run you over” mentality. I have seen them run over screaming men, women, and children while yelling out “Janabar!” and know that it is just a matter of time before I share the same fate.

When I first began going regularly, I was always a little timid, apologizing when people pushed me around, feeling like I was in everyone’s way, and feeling very exposed as everyone there could automatically spot the non-local and was suspicious as to why I was there. But since my co-worker and I have begun to have a regular presence there, our names are now called out the moment we enter, with farmers asking what we are looking for. I now feel the shugas have a “where everybody knows your name” sense of welcome to them. We still get pushed around, though.

The Armenian authentic shugas (no weekend 2-hour nonsense here) are crowded, hectic, and stressful, and I find myself dreading it when a farmer asks me to meet him or her there. At the same time, Armenian shugas are absurd, fun, and adventurous, and I guarantee they are like nothing you have ever seen before. The people there can be rude, impatient, and often try to trick people about prices and sometimes have fake scales with them. They can also be generous and often give you a little extra, are helpful, and no matter how busy they are, make the time—without fail—to ask my co-worker and I if we are Syrian-Armenians, and welcome us to Armenia. I have also seen people publicly shame those who carry fake scales. They are sometimes in active competition with each other and argue publicly and loudly, and other times work together and encourage customers to shop at their comrade’s booths.

The farmers travel to different shugas every day from their villages, organizing their areas for hours, hoping to sell all of their produce by the end of the night. They are sometimes present at two or three shugas daily, packing up and going from one to the next, depending on the time. The produce they bring is locally grown, at much better prices than any supermarket, and is usually of a much higher quality—with the soil still on the root vegetables. Visiting these shugas is a great way to see what farmers do daily to sell their produce and compete with chain supermarkets, and to see what is actually being grown in Armenia itself. While I will continue to buy imported items like oranges from Georgia every now and then, the experience really set in stone for me that buying an imported apple from a conveniently located nearby shop makes absolutely no sense when they are being grown—and sold—in Armenia.

When someone asks me about Armenian shugas or is curious to go to one, depending on the day and experience, I end up giving them completely opposing ideas, encouraging them to come but also warning them relentlessly. I tell them about the “closed” shuga, the option most tourists opt for that is all indoors, where every person has their own table with their produce laid out. This is where things are neat, calm, have a clear system, and where you will also find items that are in no way grown in Armenia, such as avocados and bananas. I describe this one as the “safe” shuga, where stray cats are even kicked out to keep the area as seemingly clean as possible. I used to think these were the authentic shugas, when a co-worker brought me to one, until I ventured outside and saw for myself the reality of the shuga-unplugged.

I have visited six in different areas, but once heard the rumor of the 24-hour shuga outside of Yerevan, as well as the one that begins at 4 a.m. I knew I had to see them for myself. I went with the only expectation (or hope) that it could not be more chaotic than the ones I had been to, and ventured out with my co-worker in the middle of the night, with flashlights, notebooks, and canvas bags. The 24-hour one was absolutely huge, with most farmers coming with their trucks full of produce, and where trying to buy five kilograms of tomatoes was met with laughter, as they explained that you buy things here in tons, or “meshoks.” The one that began at 4 a.m. was a little eerie, and those flashlights were definitely needed, but I noticed that it also had the “safe” closed option.

I realized one day that my experience with the shugas, and my inability to explain them without sounding like two different people, was, for me, largely representative of Armenia itself. On a good day, when someone would ask me why I chose to stay in Armenia, what I would hear coming out of my mouth sounded like something you would find in a tour guide book—a very romantic image of a place. On frustrating days, when my sister would e-mail me asking about coming to visit, my three-page response would be banned from her work address (company name withheld) because it violated their “language policy.”

To say it is a different experience than going to the ones in Canada is an understatement. However, I find myself somehow preferring the Armenian version, with all of its disorganization and absurdity, as there is something so much more authentic and incredible about it. In many ways, I feel that the contradiction of the shugas represent my entire relationship towards Armenia itself—where you take the positive with the negative, and simply look at it as a real place with real problems, but where, more often than not, spectacular examples of generosity, strong will, and kindness greet you. The shugas are also a harrowing and important reminder of what farmers must do daily in order to sell their produce. This was the main reason behind co-founding Go Green Armenia, where the aim is to support farmers by buying, marketing, and delivering their produce directly to people in Yerevan, making it as convenient as possible to buy locally grown produce.

As chaotic as these shugas may be (they are not for the faint of heart or those prone to claustrophobia), you learn to take the good with the bad and go there for adventure, and begin to understand what the lives of Armenian farmers entail. To those curious to see the shugas first-hand in all of their glory, here’s some advice: Know the Russian names for corn, tomatoes, potatoes, and lettuce. Always carry small change with you. Don’t go in with too much stuff (you will be pushed around relentlessly). Always, always look over your shoulder, and when you hear the word “Janabar!” don’t think twice—just run!