Miscellaneous Memories of Echmiadzin

By: Ara Ghukasyan | Posted on: 09.11.2012Warning: Undefined array key "ssba_bar_buttons" in /home/u108981792/domains/ardziv.org/public_html/wp-content/plugins/simple-share-buttons-adder/php/class-buttons.php on line 602

Warning: Undefined array key "ssba_bar_buttons" in /home/u108981792/domains/ardziv.org/public_html/wp-content/plugins/simple-share-buttons-adder/php/class-buttons.php on line 602

Warning: Undefined array key "ssba_bar_buttons" in /home/u108981792/domains/ardziv.org/public_html/wp-content/plugins/simple-share-buttons-adder/php/class-buttons.php on line 602

Warning: Undefined array key "ssba_bar_buttons" in /home/u108981792/domains/ardziv.org/public_html/wp-content/plugins/simple-share-buttons-adder/php/class-buttons.php on line 602

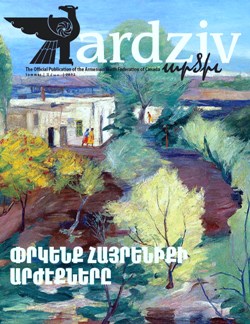

I was born on a cold mid-winter day in a hospital with no heating—or so I have been told. Nearly all of my memories of life in Armenia are confined to the small three-year period prior to my parents’ emigration to the United States, during which time my sister and I lived in the suburbs of Echmiadzin with our grandparents.

Though a “suburb” is the appropriate description, it was considerably more urban than the suburb where we lived normally. I make this distinction by virtue of the number of naked children seen out on the street on a daily basis. Most of them (around four to seven years old) were by no means naked in the Christian Children’s Fund sense, but were casually undressed down to their underwear whilst searching the streets for something to play with. Nonetheless, the small dead-end street (ending at our house) was a close-knit community of workers, friends, gossipers, seedeaters, loan givers, loan takers, and just ordinary people. By contrast, the children on my grandparents’ street were almost always fully dressed (Vartevar was a special occasion) and the neighborhood, in general, was a more stable one—socially and structurally (my home street looked like it was a breath away from falling apart).

I remember my grandparents’ house being curiously located at the centre of a seemingly endless stretch of homes that were attached at both sides. According to the unwritten code of the neighborhood kids, the allotted playing area, which was usually the distance between the two furthest kids in either direction during a game of hide and seek, was about seven houses to the right of my grandparents’ and about thirteen to the left of it. Despite spending six days a week in that street from age five to age eight, there were few occasions of venturing further than the area that we were accustomed to. But I do remember, more often than not, receiving a scolding for any time that I did and was caught.

Although the custom of prolonged streetside seating is only survived in Canada by older European women who spend countless hours around a table in their garage—with the door open, of course—most of the houses in Echmiadzin had some kind of bench in the front, which was reserved for this purpose. Perhaps the custom is better credited to the fact that some houses in West Asia and in Europe have front doors that are much closer to the street than those of their counterparts in North America. Nonetheless, it is important to note that around each bench was a field of scattered seed shells, and this was yet another means of determining how neglected the neighborhood was: clean benches and bench surroundings meant that the inhabitants hadn’t entirely relinquished hope of revitalizing their neighborhood, and vice versa. A poetic and somewhat of a naive analysis would dictate that these benches had become a sort of “social window”, and although the lonelier of the crowds were subject to a more literal interpretation of that metaphor, those in the streets with more connected social lives focused less on what went on in front of them and more on what their conversational partner told them about the happenings of the neighborhood.

I remember one particular time when I was sitting on one of my neighbor’s benches and swinging my feet, and eventually decided to see how far across the street I could fling my shoe. However, forgetting one of the more common contingencies of a street—the occasional car—I flung my slipper with just the right accidental timing to allow it to hit the door of a car that was crossing my vision. The car stopped immediately, as if expecting the projectile. The driver cried a few insults in my direction, and then drove away. I walked to up to the street to retrieve my shoe and continued over to the other side, making my way back to my grandparents’ home along the adolescent cherry trees that were planted in a line parallel to the road. I remember, strangely, that I’d developed a taste for the leaves of these trees, despite finding them bitter and repulsive at first. More curiously, however, and ironically perhaps, is the fact that there were no seed shells anywhere near that bench.

There was an old woman who lived in a small house just off our street—she was the source of almost all of the sunflower seeds in the neighborhood. Known to everyone by their Russian name, semuchka, sunflower seeds were as common and arguably as much of a cultural habit as cigarettes; leaving in the wake of their consumption a swarm of shells, as opposed to tar-soaked butts. A hundred dram and a ten-minute journey from the centre of our street was all that one needed to get enough seeds for a good three-hour, three-person, conversation. They were sold in small, medium, and large newspaper cones, the construction of which was an enigma like no other – definitely a league above that of paper planes. Perhaps there is a drop of irony in the fact that the greatest catalyst of gossip and informal dialogue came (and maybe still does come) wrapped in what was otherwise the most formal method of information delivery. Obviously no one ever read the newspaper pages that the seeds were packaged in, there were plenty of intact newspapers around after all, but I can’t help but wonder if we would have been better off if we had the curiosity to.

As a precautionary measure, the generalization of “all stray dogs are vicious” was commonplace—and rightfully so. But of course this was a favorite scapegoat for any particularly sadistic people, adults and kids, who wouldn’t pass up the chance to take a slingshot and have a go at the dogs—be they a stray or someone’s pet. It was thanks to the stray dogs and cats of the neighborhood that nightfall was an especially ominous occasion. The cats of the nighttime were a more psychological kind of horror for the neighborhood kids, mostly because almost all cats look black in the dark and because they appear and disappear in complete silence. However, as a mere emotional problem, this was easily dismissed by anyone who wasn’t instilled with the nightmarish torment of superstition at a young age. The greatest actual threat that a cat could possibly pose was the transmission of fleas or mange—about ten percent of us at that time had lice, anyway. Dogs were a different story, because, unlike cats, there is a much larger variety of sizes and shapes that dogs can come in, and so nearly every silhouette of a legged creature, draped against the asphalt and propped upright by scattered streetlights was potentially a vicious and territorial canine that was waiting to give chase and sink its filthy teeth into our backsides as we ran. Even knowing that running wasn’t a good option (all it did was provoke the animal), there was little the mind of a six-year-old could do but run, when faced with the entirely physical threat of angry, stampeding jaws.

It’s interesting how we were terrified of being bitten by dogs in the night, while kids in the West were (and probably still are) much more scared of vampires, zombies, and werewolves (I wonder if such a thing is a privilege). Consequently, another one of my most lucid memories is the graveyard that was a few minutes behind my grandparent’s street. I’d only go there in the day, but having grown very accustomed to its solemn and lonely peacefulness, I developed a love for it—still finding it very inviting and comforting, even in the common horror-film setting of nightfall. At the time, however, peace wasn’t really why I went there so often. It was arguably the greatest thrill of my daily life to ride my bike toward the graveyard and arduously pedal up the inclined road that was adjacent to it. Then, turning around and releasing the break, I’d accelerate downward with a force that would propel me halfway back the way I’d come—sometimes catching the attention of dogs that gave chase at the sight of me. This activity was among many forbidden by my grandparents, but, in regular fits of childish rebellion, I’d go over there as often as I could. Such was the nature of all my secretive excursions back in Echmiadzin.