FOUR YEARS LATER The Assassination of a Journalist in Turkey

By: Daniel Ohanian | Posted on: 02.01.2012Warning: Undefined array key "ssba_bar_buttons" in /home/u108981792/domains/ardziv.org/public_html/wp-content/plugins/simple-share-buttons-adder/php/class-buttons.php on line 602

Warning: Undefined array key "ssba_bar_buttons" in /home/u108981792/domains/ardziv.org/public_html/wp-content/plugins/simple-share-buttons-adder/php/class-buttons.php on line 602

Warning: Undefined array key "ssba_bar_buttons" in /home/u108981792/domains/ardziv.org/public_html/wp-content/plugins/simple-share-buttons-adder/php/class-buttons.php on line 602

Warning: Undefined array key "ssba_bar_buttons" in /home/u108981792/domains/ardziv.org/public_html/wp-content/plugins/simple-share-buttons-adder/php/class-buttons.php on line 602

By: Daniel Ohanian

January 19, 2007. Istanbul, Turkey. At this place and on this date, a middle-aged man in a black suit was shot dead at point-blank range. The three gunshots that shattered the cool air that day sent shockwaves through his country and the world at large.

Before looking into the identity of this man and the significance he had in life and in death, it is fitting to take a step back and take a good, long look at the city where he lived and died. Istanbul can be described as a crossroad between East and West, where the mystic Orient melts smoothly into the hustle and bustle of European urban centres. It can also been seen as a panicked metropolis caught between two competing identities, a microcosm of issues that plague Turkey at large. Both visions of this city hold true, and one cannot understand the assassination of Hrant Dink without understanding the society – and the city – where he lived and in which life was taken from him.

Dink, ethnically Armenian, was the editor of Agos, a bilingual Turkish-Armenian newspaper. When Agos was founded in 1996, many realised that drastic changes needed to be made within Turkey’s politics and society if it was to become a democratic country. However, he became one of the very few individuals who would put themselves in danger in order to make that dream a reality.

He spoke out bravely about the need for democratisation, respect towards the freedoms of expression, press and assembly, and sought to dispel the strong taboos against discussion of the Armenian Genocide and Turkey’s Kurdish citizens. For his activism, he was prosecuted under Article 301 of the Turkish Penal Code, an oft-condemned censorship law that grants the Turkish government the legal authority to imprison anyone who “publicly denigrates the Turkish nation, the Republic or the Grand National Assembly of Turkey”.

As a result of three very public trials, Dink found himself at the receiving end of a large-scale intimidation campaign. He received death threats (which were ignored by the authorities) and a constant stream of hate clogged his inbox and telephone line. In his last editorial he wrote, “The judge had made a decision in the name of the ‘Turkish nation’ and had it legally registered that I had ‘denigrated Turkishness.’ I could have coped with anything but this. […] Those who tried to single me out and weaken me have succeeded.”

Hrant Dink was murdered by Ogun Samast, a 17 year old Turkish youth who had travelled 900 km to kill the journalist. After his arrest, Samast was photographed posing with a Turkish flag, flanked by two proud-looking policemen. Four years after the crime, observers of Turkish judicial law note that Samast may be released if the murder trial – already criticised for its slow pace – isn’t wrapped up by 2012.

Insufficient Half-Measures

What has changed since January 2007? Within the administration, not much at all. Some notable stories that made headlines are the imprisonment of a 15 year old Kurdish girl who was found guilty of throwing rocks during a political rally, the possible banning of Facebook (YouTube has been blocked since 2007), and the proposed dismantlement of a Turkish-Armenian friendship statue.

For over a century, successive Turkish governments have been using shallow half-measures to appease foreign observers and to feign true democratisation. Homogenisation of the Anatolian peninsula through suppression of ethnic diversity is not a new state policy. After most Armenians, Greeks and Assyrians had been eliminated by Ottoman leaders during the 1914-1923 genocide, the new Republic focused its attention upon its Arab and Kurdish citizens, subjecting them to policies of forced assimilation.

Use of the Kurdish language in the public sphere was illegal from 1925 to 1991. Fortunately, over the past 20 years, some new policies have appeared to give Turkey’s Kurdish minority equal standing with their fellow citizens of Turkish ethnicity. However, Prof. Amir Hassanpour of the University of Toronto looks beneath the surface: “No one can deny that this is a different Turkey. There is, for example, Kurdish broadcasting by the government on a limited scale. One should appreciate that it is now possible for media to be published in Kurdish – it is no longer a crime against the state. What has not changed, however, are the government’s assimilation policies. These new ‘rights’ are a way to satisfy the European Union, but to maintain the linguicidal policy.”

According to a recent Human Rights Watch report, although Kurds now have the “right” to their own press, newspapers continue to be shut down and their journalists incarcerated based on fictitious ties to terrorism. Another such “right” is the legalisation of Kurdish-language education, a development which is handicapped, says Dr. Hassanpour, by three strict preconditions: lessons must be given only on weekends, when kids have little incentive to study; teachers must be approved by the government, ensuring that the state’s nationalist discourse is not challenged; and students must be over 12 years old, ensuring that they are brought up “Turkish” during their key formative years.

Winds of Change

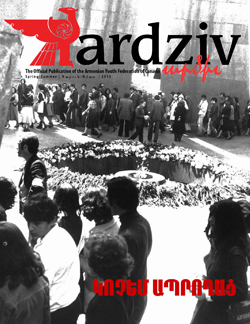

Within Turkish society, the development of a conscious and reflective populace can be seen and has to be encouraged. During Hrant Dink’s funeral, 100 000 people marched down the streets of Istanbul carrying placards which read “We are all Armenian” and “We are all Hrant Dink.” His weekly newspaper, it should be noted, was a meagre 12 pages long and had a subscriber base of only 6 000 readers in a country of 70 million. Yet his words rang loudly against the oppressive taboos of the Turkish government and conservative society.

Before his death, in September 2005, a conference about the Armenian Genocide was held at Bilgi University for the first time ever. Originally set for May, it had to be rescheduled and relocated after the justice minister made charges of treason against its organisers and the courts attempted to censor the speakers. Since 2007, similar events have included a celebration of the work of Armenian composer and Genocide victim Gomidas, an exhibition of Armenian architecture, and four separate – though painfully small – Genocide commemoration events in Istanbul.

In recent years, crypto-Armenians have been gradually coming out of hiding and openly acknowledging their Armenian lineage. One of the most moving examples of this is written about in My Grandmother, a book by lawyer Fethiye Cetin. She tells of how her grandmother, at the age of 90, reveals to her that she is in fact an Armenian, abducted as a young girl from a deportation caravan in the desert and married off to a Turkish man. Having received unprecedented popularity, Cetin’s book is now in its 7th edition.

In Dink’s absence, his vision of Turkey continues to be pursued by other outspoken members of Turkish society. Among them are Ragip Zarakolu and his late wife, who have been taken to court over 40 times for the books they publish; Nobel Laureate Orhan Pamuk; Hrant’s son, Arat Dink; and Hasan Cemal, grandson of a genocide mastermind who has drawn attention to and denounced the policies of his ancestor. These intellectuals are slowly overcoming the monolithic taboos that have fragmented Turkish historical identity and are paving the way for a new – and more honest – Turkey.

Reflections

Although Hrant Dink died four years ago, his memory and legacy live on. Every year following Dink’s assassination, thousands have gathered outside his office. They stand together not only to commemorate, but also to show the state that they have not forgotten the way in which their government betrayed their fellow Istanbulu.

As we commemorate Hrant’s death every January 19th, we cannot help but look back as we move forward. There must come a time when instead of immortalising genocidaires by naming streets and erecting statues in their honour, the government of Turkey will choose to celebrate the true heroes of its history: the hundreds of Turks and Kurds who saved Armenians in 1914-1923.

Only through honest introspection can Hrant Dink’s dream be realised: a Turkey which accepts its past and respects the rights of all its citizens, regardless of ethnicity. In the meantime, we wait with bated breath, wary of when the next gunshot will ring.